The Effect of Age and Gender on Work Preferences

15 August 2023

In the ongoing conversation about workplace behaviour, a recurring question is whether demographic factors such as age or gender influence how people prefer to work. Team Management Systems (TMS) has explored this question through decades of research. The aim has never been to categorise, but rather to create thoughtful dialogue and expand self-awareness.

This article revisits findings drawn from a global dataset of over 500,000 individuals who completed the Team Management Profile (TMP) prior to 2022. From that year, TMS ceased collecting both gender-specific and age-specific data. This change reflects a deliberate commitment to inclusive, ethical practice and a broader understanding of identity and privacy in modern workplaces. The patterns described here are therefore shared in the context of historical trends. They are not prescriptive, but instead offer useful reflections for those engaged in leadership development, coaching, and team facilitation.

Historical Gender Patterns in Work Preferences

Across a sample of 476,879 respondents who provided gender information, the overall differences in work preferences were small. Men scored slightly higher on the Analytical dimension of the Analytical–Beliefs scale. Women, on average, scored marginally higher on the Practical and Beliefs dimensions. While statistically significant, these differences were subtle and are unlikely to be meaningful in most workplace applications.

More notable is the consistent reliability of the TMP across gender. Internal consistency, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha, was strong in both male and female samples. In fact, female respondents showed slightly higher reliability scores. In simpler terms, people of all genders answered TMP questions in ways that formed consistent and meaningful patterns. The results were dependable, and the profile functioned equally well for everyone. This adds confidence to the interpretation of TMP results, regardless of the respondent’s gender.

Role Preferences by Gender

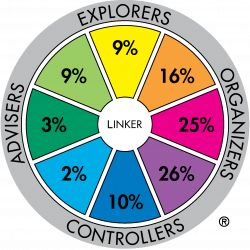

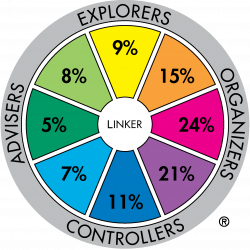

When looking at the distribution of role preferences across the Team Management Wheel, the patterns among men and women were remarkably similar. The roles most frequently identified as "major" did not differ greatly between groups.

This reinforces a central principle of the TMS framework: work preferences are not defined by demographic labels. Rather, they emerge from individual personality, life experience, and values.

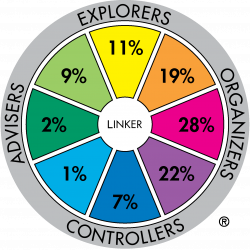

Figure 1. Major role preference distribution for worldwide Male sample (n=276,671)

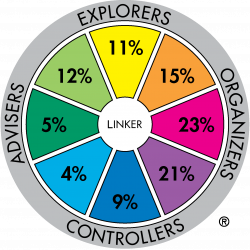

Figure 2. Major role preference distribution for worldwide Female sample (n=200,208)

Age as a Factor in Work Preferences

Age, by comparison, appears to show a more noticeable influence on work preferences. Although still modest, the differences observed across age groups are more consistent and have practical implications.

As individuals age, several trends emerge:

-

A gradual shift towards Introverted preferences

-

A stronger orientation towards Beliefs, accompanied by a decline in Analytical preferences

-

An increasing preference for Structure

-

A slight rise in Practical preferences

Some may view this as a move towards conservatism. Others may interpret it as the result of accumulated experience and a clearer understanding of what matters most in work and life. Either way, the data suggests that preferences develop over time.

Considerations in Interpretation

This research is cross-sectional. It compares people of different ages at a single point in time. It does not track individuals as they age. As such, some differences may be shaped by generational influences rather than the ageing process alone.

Still, the trends offer useful insights into how people approach their work at different life stages.

Role preference data further supports these patterns. Individuals under 30 were more likely to align with roles such as Explorer–Promoter and Creator–Innovator, which reflect high energy, creativity, and interpersonal engagement. Older respondents, especially those aged 50 and above, more often reported preferences for roles such as Upholder–Maintainer and Concluder–Producer, where structure and delivery are central.

This progression may reflect a growing alignment between personal values and the type of contribution people choose to make later in their careers.

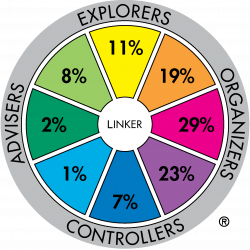

Figure 4. Major role preference distribution for worldwide age group sample: under 20 (n=994)

Figure 5. Major role preference distribution for worldwide age group sample: 20-29 (n=56,521)

Figure 6. Major role preference distribution for worldwide age group sample: 30-39 (n=114,034)

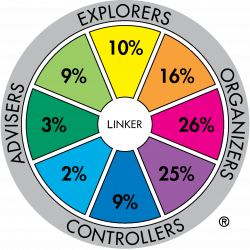

Figure 7. Major role preference distribution for worldwide age group sample: 40-49 (n=99,649)

Figure 8. Major role preference distribution for worldwide age group sample: 50-59 (n=45,951)

Figure 9. Major role preference distribution for worldwide age group sample: 60-69 (n=5,703)

Figure 10. Major role preference distribution for worldwide age group sample: 70-79 (n=150)

From Research to Reflection

These findings are not presented to suggest limits or fixed pathways. Rather, they offer a lens for reflection. For facilitators, coaches, and team leaders, age-related trends can be useful in understanding how individuals may approach work over time.

For instance:

-

A younger Creator–Innovator may seek autonomy, flexible structure, and opportunities for idea generation.

-

An older Concluder–Producer may be energised by systems that allow for predictability, consistency, and delivery of results.

-

In diverse teams, recognising generational variety can help create understanding, build psychological safety, and improve collaboration.

The TMP is not a tool for classification. It is a framework for conversation. It helps individuals reflect on who they are now, and how they might evolve or adapt as their work and life contexts change.

Final Reflections

Work preferences are shaped by many forces. Historical gender data shows that differences between men and women are minimal, and the reliability of the TMP holds across groups. Age, meanwhile, appears to have a small but observable influence on how preferences shift across life stages.

Since 2022, TMS has ceased collecting both gender and age data. This decision supports a broader movement towards inclusive, future-focused practice. It also affirms TMS’s commitment to understanding individuals not through static demographic categories, but through the complexity of their lived experience and workstyle preferences.

The TMP continues to offer a powerful framework for exploring how people engage with work. As individuals grow and their perspectives deepen, their preferences may shift. The role of the TMP is to support that journey with clarity, insight, and respect.

References:

- Davies, R.V., (1988/89), The Margerison-McCann Team Management System: Research Manual 1988/89, Graduate School of Management, University of Queensland.

- Team Management Systems (1998), Team Management Systems Research Manual: Second Edition, Brisbane, Australia.

- McCann, D.J., & Mead, N.H.S., (Eds.), (2003), Team Management Systems Research Manual: 3rd Edition, Team Management Systems, Brisbane, and York.

- McCann, D.J., & Mead, N.H.S., (Eds.), (2018), Team Management Systems Research Manual: 5th Edition, Team Management Systems, Brisbane, and York.